This story was produced in collaboration with Capital & Main, a nonprofit media publication focused on inequality, and was made possible with funding from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

As a child, Ashley Hernandez remembers pretending that the oil pumpjacks that loomed over her neighborhood were dinosaurs. Other children in her community called them giraffes, or horses. The strange metal animals pecked rhythmically at the earth, sandwiched between homes, next to playgrounds, in the parking lots of grocery stores, sucking the oil from the sediments beneath her neighborhood of Wilmington in southern Los Angeles.

Hernandez also remembers the nosebleeds. She would get them at night, and they were intense — not a trickle of blood, but so heavy that her mom would often tell her to try not to bleed through her pillows.

The nosebleeds weren’t the only thing. Kids and teachers at her school would get cancer diagnoses — a lot. She remembers being scared of the noise that was made by the strange device that her mom would use at night — a nebulizer, to treat her asthma. Adults would tell her not to drink the tap water. And there were periodic warnings to stay inside because of explosions at nearby refineries.

It wasn’t until she was in high school that Hernandez started to learn about the possible connections between the nosebleeds, the cancer, the asthma, the undrinkable water, and the oil.

Wilmington and the neighboring community of Carson are home to five oil refineries, as well as the Wilmington Oil Field — the third-most productive patch in the United States. More than 3,400 onshore wells have been drilled in the field since oil was first discovered there in 1932; today, the site pumps out 46,000 barrels per day from 1,550 active wells. Wilmington is also home to more than 50,000 residents, more than 90 percent of whom are people of color. Due to the impact of the oil and gas drilling and refining, census tracts in Wilmington are exposed to more pollution than 80 to 90 percent of the state of California. Meanwhile, predominantly white Palos Verdes — some 12 miles west of Wilmington, on the other side of Interstate 110 — is exposed to less pollution than 85 percent of the state.

Hernandez herself grew up only 600 feet from a drilling site run by a subsidiary of Warren Resources. The site has 90 active oil wells that operate 24 hours a day. The wells are loud and emit noxious odors — sometimes the smells evoke rotten eggs, she explained, other times they’re sickly sweet. “A lot of our experiences on the front line are a physical attack on our body,” said Hernandez.

Hernandez is one of millions of Californians affected by neighborhood drilling — the practice of exploring for oil right in the middle of communities, next to the places where people live, study, and seek medical care. The phenomenon disproportionately impacts low-income communities and communities of color, and creates an environmental health nightmare for those living in its shadow.

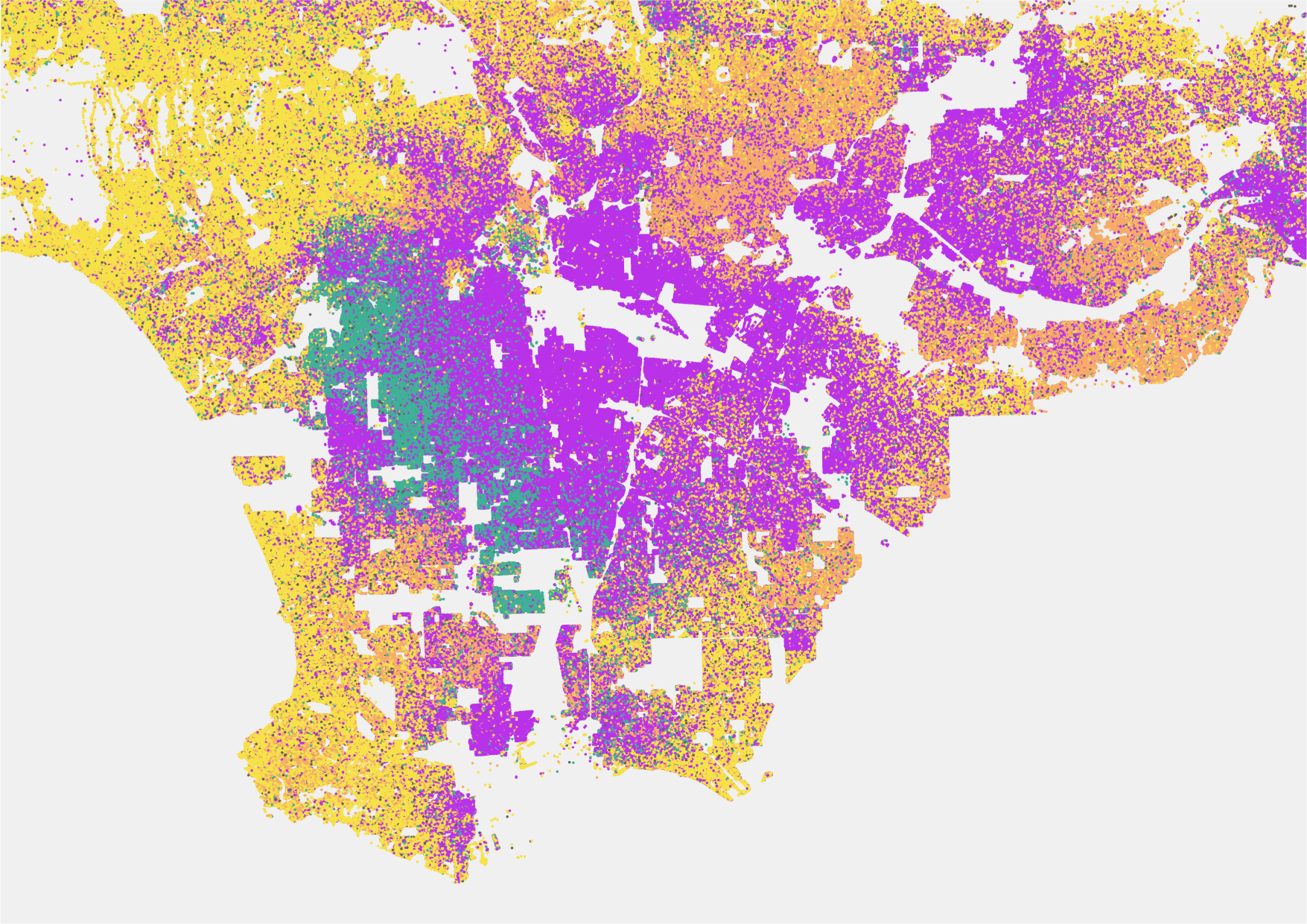

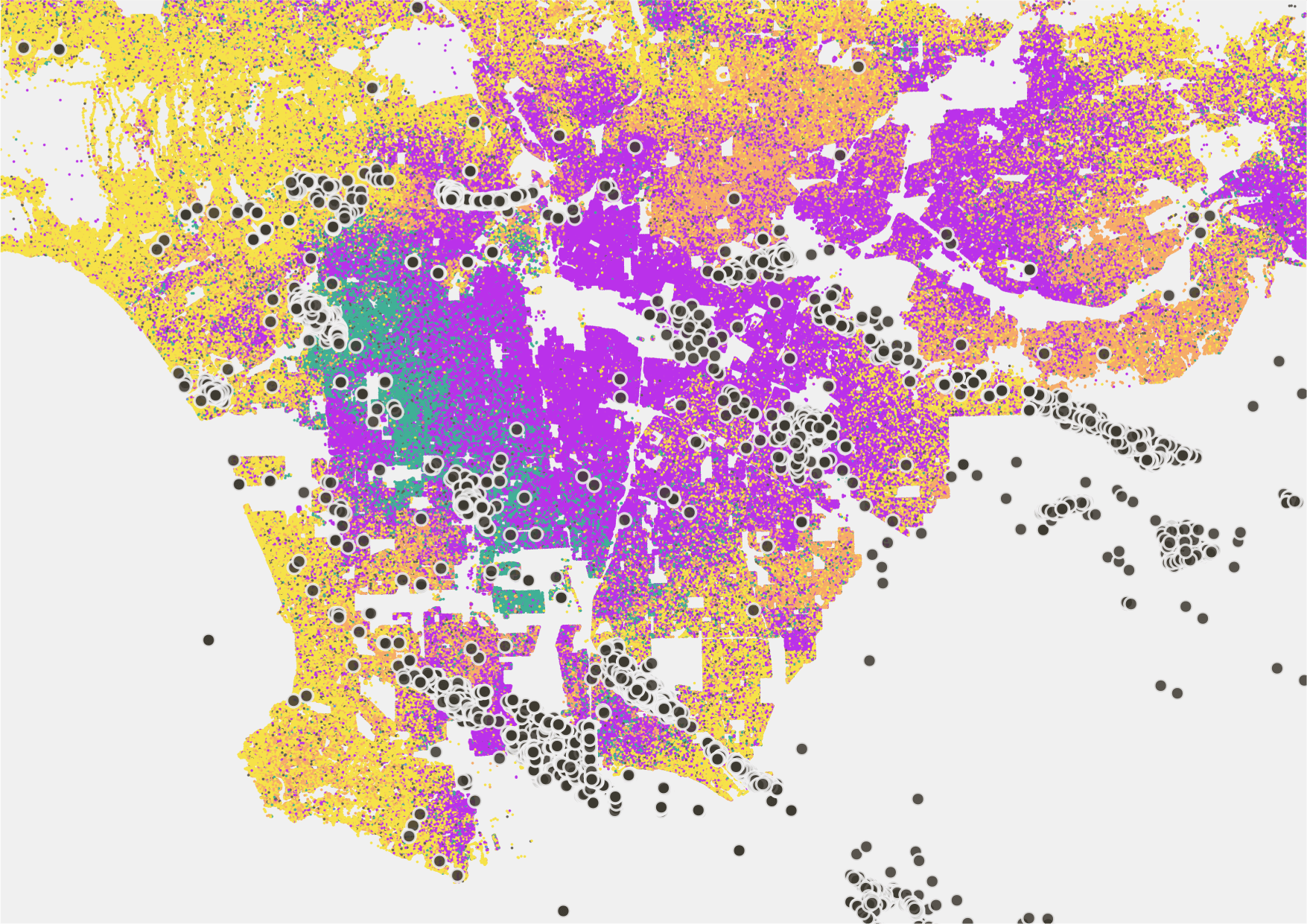

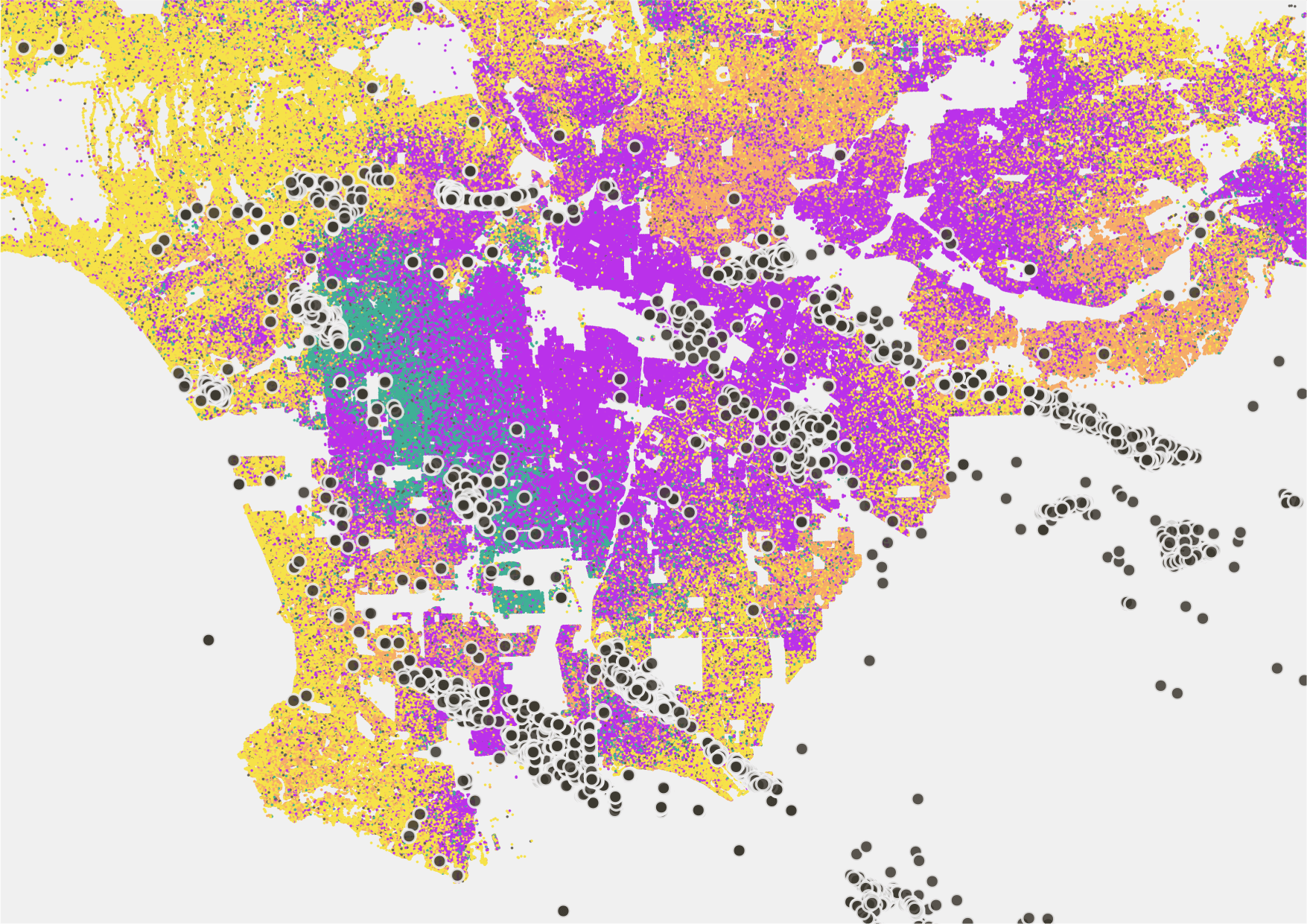

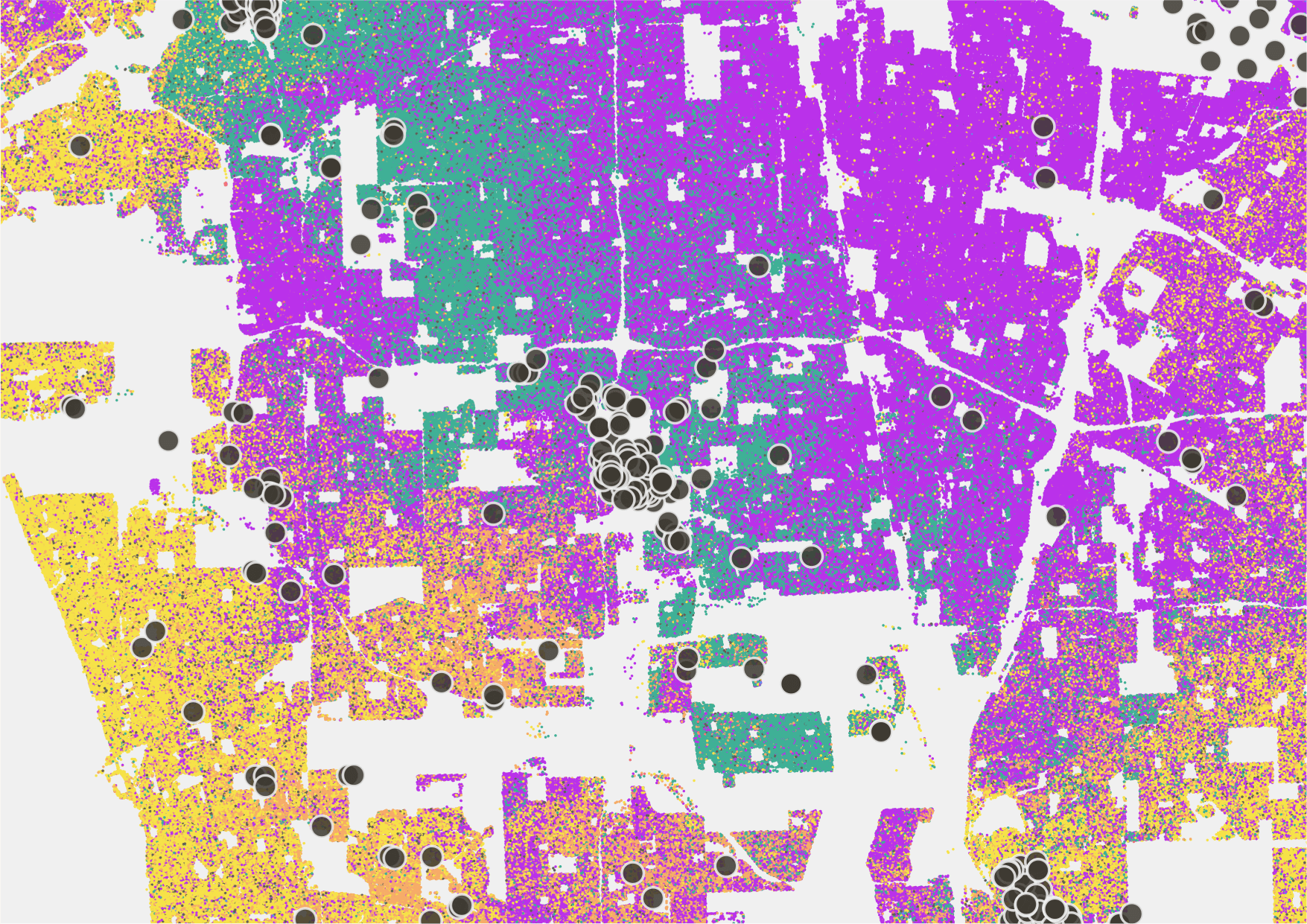

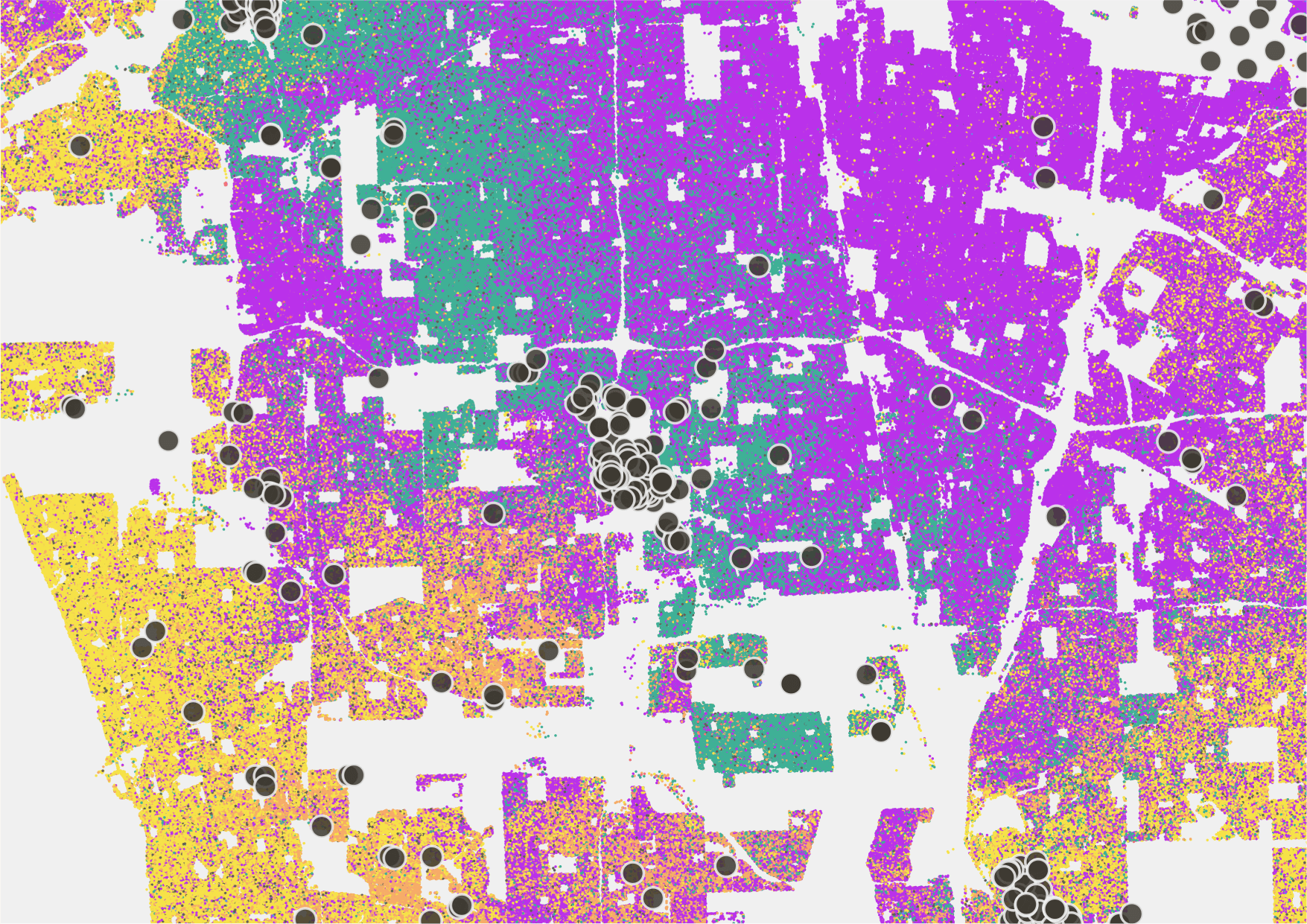

- Asian

- Black

- Hispanic

- Native American

- Pacific Islander

- White

- Oil or gas well

- Asian

- Black

- Hispanic

- Native American

- Pacific Islander

- White

- Oil or gas well

- Asian

- Black

- Hispanic

- Native American

- Pacific Islander

- White

- Oil or gas well

- Asian

- Black

- Hispanic

- Native American

- Pacific Islander

- White

- Oil or gas well

- Asian

- Black

- Hispanic

- Native American

- Pacific Islander

- White

This is south Los Angeles County. Every dot represents one person who lives there and, roughly, where they reside.

Los Angeles County has no required setbacks protecting residents from oil and gas wells, which are sited in close proximity to homes, schools, and medical facilities.

But some Los Angeles County residents tend to live closer to wells than others.

Compare the area around Compton, which is majority Black and Latino, to predominantly white Manhattan Beach to its west.

The stark contrast in exposure to wells between majority white enclaves and those where people of color live is replicated across the state.

Despite California’s reputation as an environmentally friendly state, neighborhood drilling is a distinctly Californian phenomenon. Most oil-producing states — including Colorado, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Wyoming, and even Texas — have regulations dictating how close to homes, schools, and sometimes hospitals that oil wells are allowed to operate. This buffer zone between oil wells and the areas where people live is known as a setback.

Without statewide setback rules, the regulatory landscape varies dramatically at the local level. Some counties have no setback rules at all, while others, like Ventura County, have setbacks of 1,500 feet from homes and 2,500 feet from schools for new wells. California’s regulatory body for oil and gas, the California Geologic Energy Management Division, or CalGEM, is currently in the process of drafting a public health rule that could include statewide setbacks.

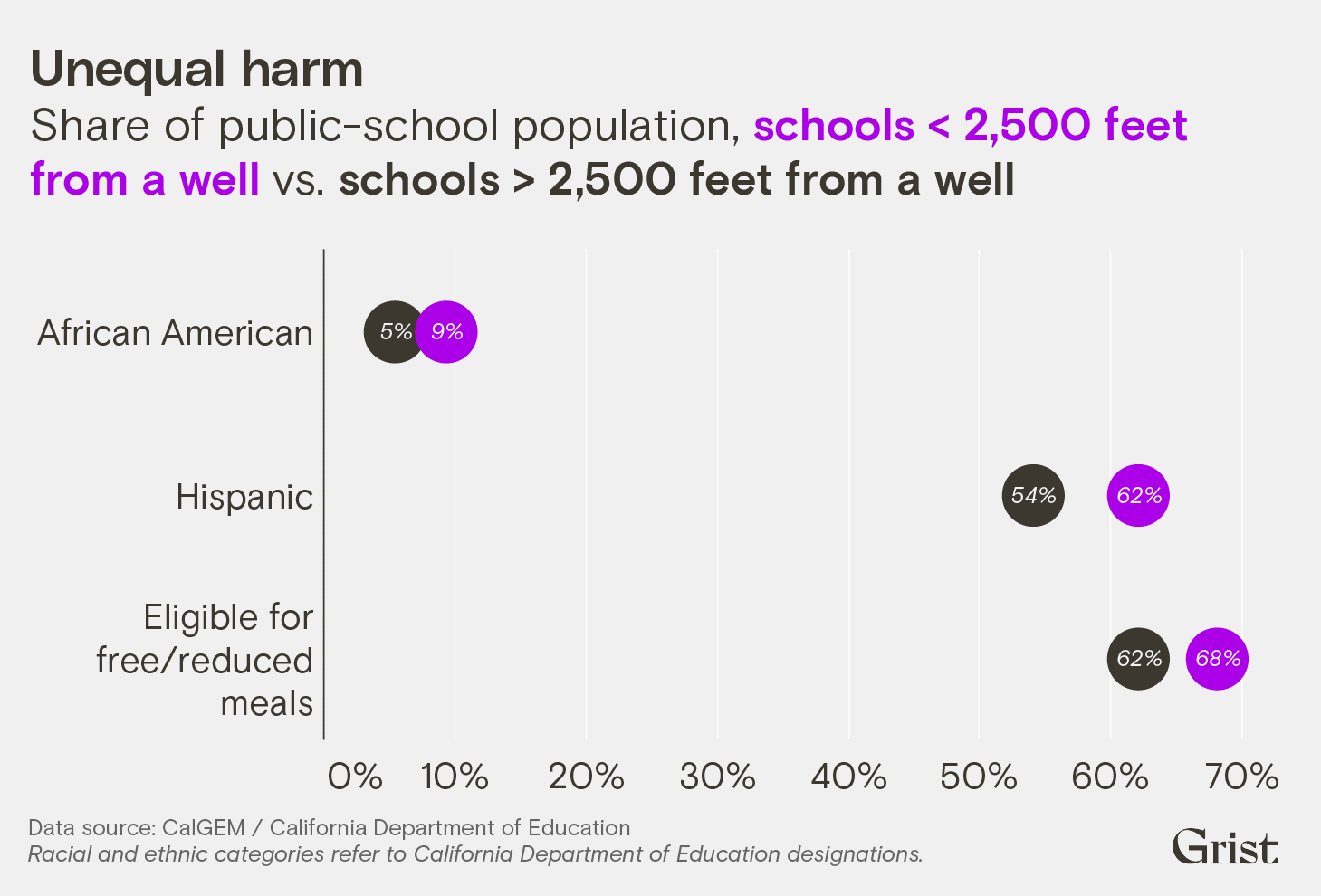

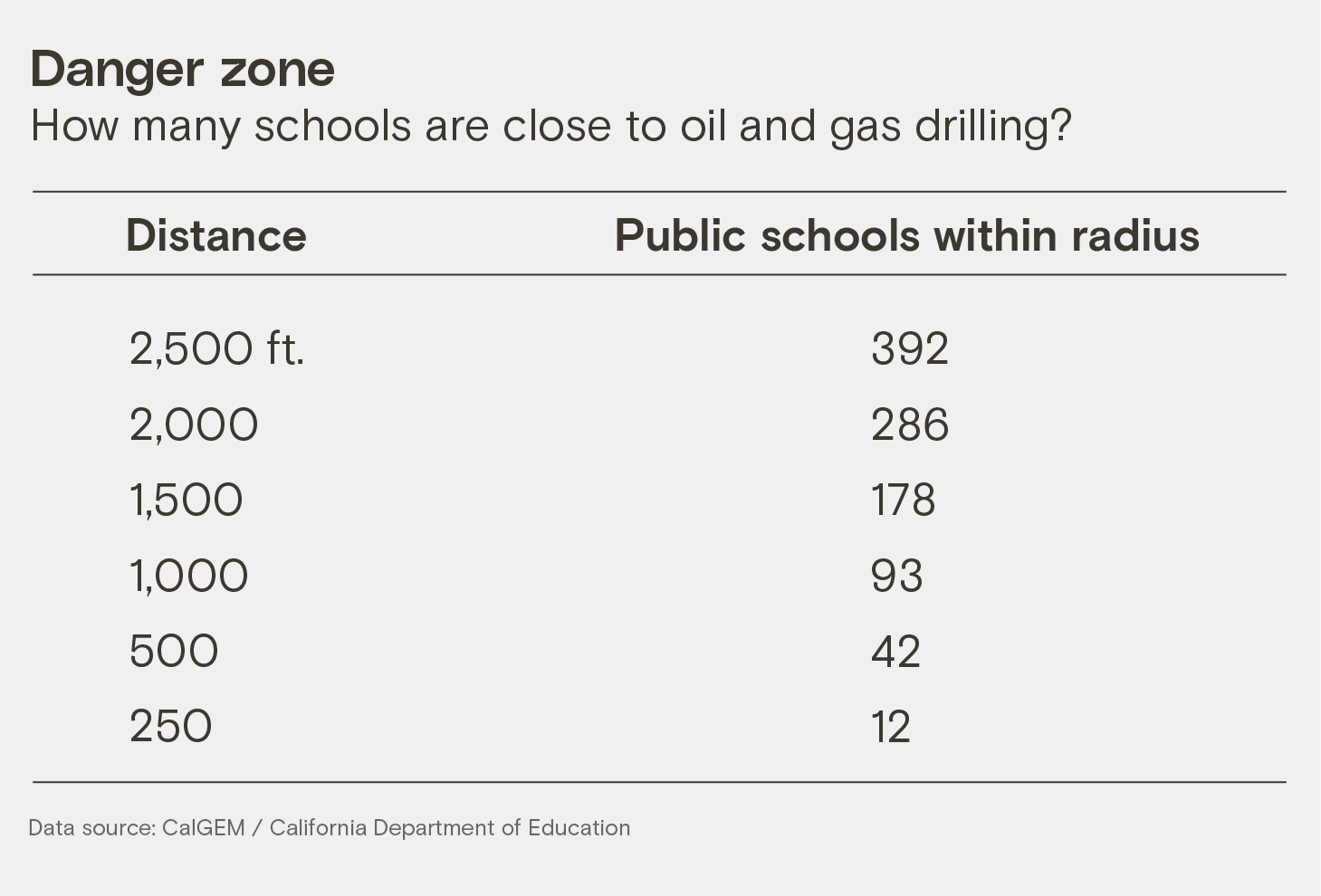

A Grist and Capital & Main analysis shows that communities around hundreds of schools statewide, which disproportionately serve low-income students, students of color, and medically underserved populations, would immediately see the benefits if CalGEM instituted setbacks. Of course, the number of people protected depends on how far the agency mandates that oil drilling can take place from a home, school, or hospital.

Grassroots advocacy groups like Communities for a Better Environment — where Ashley Hernandez now works as a youth organizer — Stand Together Against Neighborhood Drilling, and Physicians for Social Responsibility – Los Angeles have been pushing for setbacks to protect community health for years. In 2015, a coalition of youth and advocacy groups, including Communities for a Better Environment, sued the city of Los Angeles over its practice of rubber-stamping residential oil drilling projects. The groups ultimately settled with the city, which agreed to make changes in the well permitting process.

Oil and gas extraction spews a soup of toxic substances into the air, including nitrogen oxide, formaldehyde, volatile organic compounds, hydrochloric acid, and other chemicals known to be dangerous to human health. Unsurprisingly, living in proximity to oil wells has been linked to a range of health issues — including nosebleeds like Hernandez experienced, as well as migraines, rashes, respiratory problems, and longer-term impacts on health. “There’s been a growing body of epidemiological literature trying to understand what impacts oil and gas developments have for communities living nearby,” said Jill Johnston, assistant professor of public health at the University of Southern California.

In studies of communities living near urban oil wells in Los Angeles, Johnston found that participants living closer to an oil well had impaired lung function and higher rates of asthma than those living farther away — making it quite literally harder to breathe. Living near oil and gas development, in general, has also been linked to preterm births and other adverse reproductive outcomes, as well as a host of other health problems, including higher rates of cancer and heart disease. In 2015, a report authored by the California Council on Science and Technology, a nonprofit that advises the state’s government, concluded that drilling posed health risks to communities living nearby and recommended the development of “science-based” setbacks.

Children are at special risk, said Michael Jerrett, a professor of environmental health sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, and a contributing author to the 2015 report. Children’s air intake relative to their body mass is larger than that of adults, meaning that when they breathe they “are inhaling larger doses of air toxics,” Jerrett explained.

“The capacity of these air toxics to affect and disrupt those processes that are critical to healthy childhood development is much greater,” Jerrett said. For this reason, putting oil wells “close to schools, where you have a lot of rapidly developing children, is something that is likely to elicit health effects that are putting children at greater risk.”

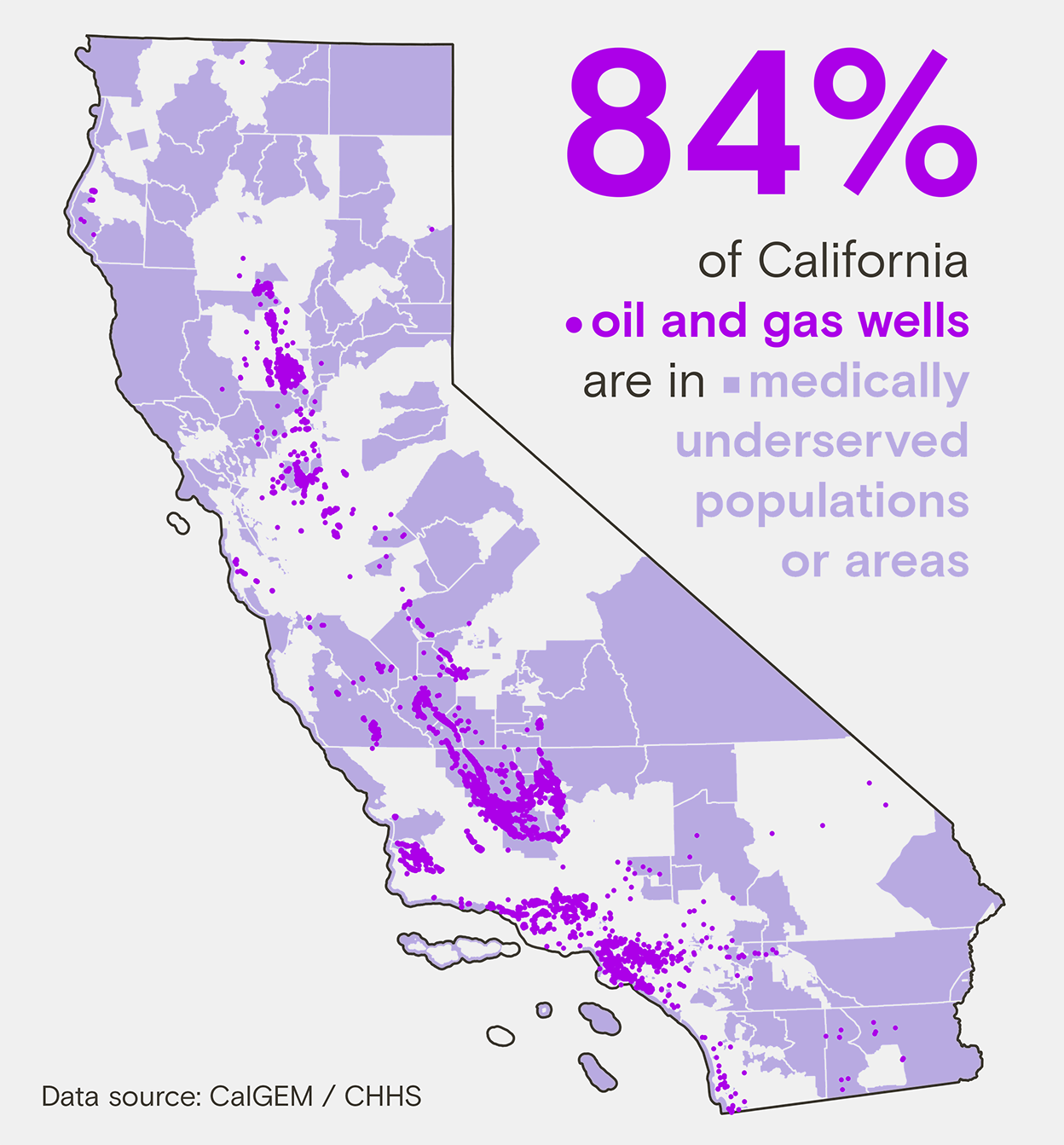

More than 7 million Californians live within a mile of oil and gas drilling operations. And 84 percent of wells in the state are located in places categorized by the federal government as medically underserved areas or populations — placing a disproportionate public health burden on communities already neglected by the health system.

Using data from CalGEM, the California Department of Education, and the California Health and Human Services department, Grist analyzed the number of oil wells near schools to help understand the impact that setbacks for oil and gas wells might have on frontline communities.

According to CalGEM data, of the 240,000 oil and gas wells in California, 98,737 are active or idle but not cleaned up, meaning that they can still emit toxic chemicals. Across the state, about 392 public schools — 4 percent of all public schools in the state — are located within 2,500 feet of a well. These schools serve a total of 258,714 students. The majority of these schools are in Los Angeles County, and they represent 13 percent of public schools in the county of 10 million people. Across the state, Black and Hispanic students are disproportionately burdened by the impact of oil and gas drilling on schools — as are students eligible for free and reduced school meals.

In the last two years, the majority-Democrat California Senate has voted down two bills that would have instituted setbacks. The first, Assembly Bill 345, passed the state Assembly before being voted down in the state Senate Committee on Natural Resources and Water last summer. The second, Senate Bill 467, was voted down in the same committee this spring.

When people think of oil country, they don’t often think of California. Yet oil played a major role in the state’s development, and oil money is entangled in California’s political system. That’s particularly true in Los Angeles, the city where the state’s oil boom first took off.

The Los Angeles basin is one of the most oil-rich basins on Earth. As such, “the exploration for oil and extraction of oil got baked into the fabric of Los Angeles,” Sarah Elkind, professor of history at San Diego State University, told Grist. A century ago, Los Angeles was “small, industrial, and isolated,” but oil development soon became the backbone of its economy. By the 1930s, Los Angeles had grown from a small city of 50,000 to a metropolis of 1.2 million that produced a quarter of the world’s oil.

Early oil development in Los Angeles was “incredibly chaotic, very dangerous, very destructive,” said Elkind. Oil fires, explosions, and hot oil gushing from the earth onto residential property were not uncommon. As the dangers of oil development became more apparent, public opposition to drilling in dense urban areas grew. Everything changed, however, during World War II. In response to the war, the federal government put pressure on Los Angeles to permit drilling throughout the city. People were so invested in the war effort, Elkin said, the oil companies got what they wanted.

Oil shaped Los Angeles — and millions there still live with the continuing legacy of that oil boom. But oil’s grip on the City of Angels could be loosening. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously in September to phase out the 1,600 oil and gas wells and ban the drilling of new wells in unincorporated parts of the county. The timetable for that phaseout is yet to be determined, and Wilmington’s wells would not be affected by the move.

Still, California is the nation’s seventh-largest oil-producing state. And as with any top oil-producing state, it has an active and powerful oil lobby. The Western States Petroleum Association, or WSPA, an oil industry group, is one of the largest lobbying forces in California by expenditure. WSPA argued in opposition to both A.B. 345 and S.B. 467, and Democratic senators who voted against both bills received thousands of dollars in contributions from the industry.

Al Muratsuchi, the state assemblymember who introduced A.B. 345, pointed to the political power of the oil industry as the culprit for the bill’s failure. “The reason why the bill died in committee with three Democrats voting against the bill is not only the political power of big oil but also the political power of the labor unions that represent workers who have a stake in the oil industry,” Muratsuchi said. “We talk a lot about how science should prevail over politics. In this case, the science is clear — but the politics prevailed.”

In response to a request for comment, a WSPA spokesperson said that the oil and gas industry does not oppose setbacks wholesale, but that “a one-size-fits-all approach for an entire state for an issue like this is rarely good public policy.”

With both A.B. 345 and S.B. 467 defeated, the most realistic pathway open at the state level to institute setbacks appears to be through CalGEM. The agency was known as the Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources, or DOGGR, until 2019. That summer, DOGGR became embroiled in scandal when it came to light that regulators were issuing permits for risky drilling projects without reviewing them first and that they held stock in the very companies they were supposed to be regulating.

In response to the scandal, the California legislature passed a law changing the agency’s name to CalGEM and updated its mandate to more explicitly include the protection of public health. In November 2019, Newsom initiated the start of updated public health and safety rules for the agency, a draft of which was promised by December 31, 2020. The rulemaking, which many hope will include oil and gas setbacks, has still not been released.

In response to a request for comment from Grist, CalGEM head Uduak-Joe Ntuk pointed to the agency’s new public health mandate and to several actions to bring its policies in line with California’s climate change goals. “CalGEM has instituted a new rigorous conflict of interest policy for all staff, embarked on racial justice training, increased transparency with new online data portals, and instituted the most rigorous review and approval of permits in the nation,” he said.

According to Colin O’Brien, deputy managing attorney for Earthjustice, a proposed rule on setbacks is a litmus test that will prove CalGEM is a reformed agency. “The name has changed, and they have a mandate now to protect health and safety,” he said. “This forthcoming rule on setbacks will demonstrate whether they take that mandate seriously.”

In the meantime, Hernandez and the other activists at Communities for a Better Environment are continuing to organize and demand that California residents be spared the health effects of living alongside oil operations. They’ve taken every opportunity to push CalGEM for 2,500-foot setbacks at the agency’s community meetings. “This is a fight for our lives,” Hernandez said.

Editor’s note: Earthjustice is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.