Road to Ruin

The Roadless Rule is supposed to protect wild places. What went wrong in the Tongass National Forest?

March 28, 2022

This project was supported by The Pulitzer Center.

The unincorporated community of Naukati Bay is home to less than 150 people. But for those who live here, it’s one of the last places in the nation where residents are able to hunt and fish to fill their freezers and sustain their families. The town has no post office and almost no cell phone service. Residents affectionately refer to the “phone booth” — a small turnout near the top of a hill a few miles outside of town, where a few signals sneak through.

Naukati Bay sits in the upper half of Prince of Wales Island, part of the archipelago that makes up Alaska’s southeast panhandle. Surrounding the town is Tongass National Forest, the world’s largest intact temperate rainforest, nearly 17 million acres spread across 1,100 mountainous islands. There’s not much to see in town, except the marina and the old steam donkey on display, an antique powered winch that was used in the early 20th century to help gather logs.

Nearly 2 million people visit the Tongass every year, coming from all over the world to marvel at the vast swaths of Sitka spruce, western hemlock, and red and yellow cedar, some towering as tall as 200 feet. They also come for the wildlife. Black and brown bears swat at spawning Pacific salmon and Dolly Varden char. Bald eagles and ravens feast on the leftovers. Humpback whales scoop up thousands of herring that spawn each spring as orca stalk Chinook salmon in the waters that divide the Alexander Archipelago. The forest is also the historical home of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian people, whose lands were stolen and then used to establish the national forest.

The Tongass has been the heart of the logging industry in Alaska for decades, starting in the 1950s with the arrival of pulp mills. It was at its zenith in 1990, employing crews in the thousands to clear-cut old growth trees. But attitudes were shifting. In the late 1990s, the federal government declined to renew a 50-year contract with a pulp mill in Ketchikan, which, along with tightening environmental and production standards, dealt a fatal blow to the largest consumer of Prince of Wales Island’s timber.

In 2001, in the waning days of his administration, President Bill Clinton issued the Roadless Area Conservation Policy, also known as the Roadless Rule. The directive was designed to restrict roadbuilding, and by extension large-scale logging and mining, on 58 million acres in the country’s national forests. For more than two decades, industry interests and resource-heavy states have challenged the policy. But the Roadless Rule has largely always prevailed, and long been heralded as a major win for conservation, helping to protect the United States’ few remaining wild places.

Except, that is, for the Tongass.

The policy’s legacy is being challenged in Alaska, where resource extraction is a key driver of the state’s politics. Governors from both parties have fought the Roadless Rule in federal court. Now, Naukati Bay and the other communities nestled within Tongass are on the front lines of the debate over clear-cutting old-growth trees in the 21st century.

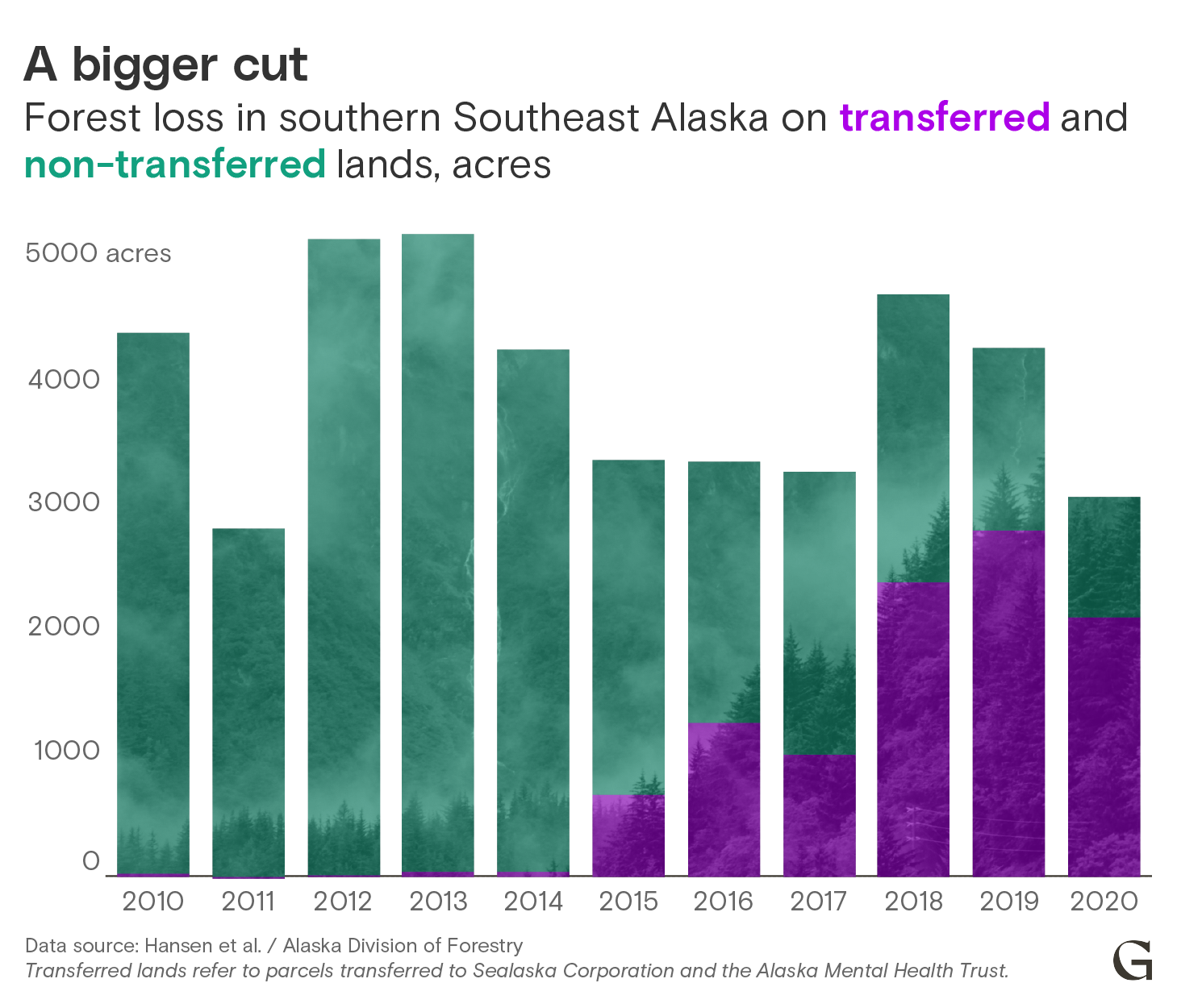

According to an analysis of satellite data by Grist and Earthrise Media, the Southeast Alaska rainforest lost nearly 70,000 acres of tree cover between 2001 and 2014. In southern Southeast Alaska — the lower half of Alaska’s panhandle — alone, that figure was close to 58,000 acres. Most of this logging, however, occurred outside designated roadless areas and federally owned lands.

From 2015 to 2020, the lower half of the Southeast Alaska panhandle saw another 22,000 acres logged. But these cuts were different: Forty-six percent of the logging over that time period occurred on parcels recently transferred out of federal ownership.

What happened? Land exchanges by Congress.

In basic terms, a land exchange is when Congress approves a swap between a parcel of federally protected forest land and tracts that have been in private hands. In some cases, this could mean a swap of old-growth forest for land that has been clear-cut or is in second-growth (and therefore less valuable). Negotiations for these arrangements can take years and involve people from government and the private and nonprofit sectors.

Land exchanges have allowed lawmakers in Washington, D.C. to bypass the Roadless Rule and other environmental protections and transfer ownership of thousands of acres of old-growth Tongass National Forest, opening the land up for logging.

A deeper look at the data from the Tongass region shows that 62 percent of the forest acreage lost between 2001 and 2014 was on state or private lands that had been transferred out of federal ownership — and by extension, oversight and management.

Recently, about 10,800 acres near Naukati were granted from Tongass to the Alaska Mental Health Trust, which is obligated — it’s in the trust’s charter — to maximize profit from its landholdings to fund social services in the state. “The trust grants more than $20 million a year to partner organizations that provide services and support to Alaskans with developmental disabilities and behavioral health conditions,” Jusdi Warner, the executive director of the Trust’s land office, said in an interview. “The immediate goals for this land exchange on the trust side is for timber harvest to maximize the revenue from the trust lands.”

The organization plans to harvest timber from the former federally protected Tongass land and sell it to two primary customers. Viking Lumber operates the last remaining sizable sawmill in Southeast Alaska and is the primary holder of large-scale timber contracts on Prince of Wales Island tracts owned by the Mental Health Trust. Its owners did not respond to a series of interview requests. According to a 2015 report, Viking’s Tongass old-growth trees go into products ranging from Steinway grand pianos to picket fences and gazebos.

The other is Alcan, a Ketchikan, Alaska-based timber outfit that exports 100 percent of its logs to Asia for milling. The company’s principal owner also declined to be interviewed. By the Mental Health Trust’s own accounting, it stands to make between $20 million and $30 million by commercially logging former Tongass parcels it’s received from the federal government. Old growth is prized by the timber industry for the quick buck; second-growth forests are a longer-term play pushed by those advocating for sustainable logging.

Here in Naukati, a community that was founded as a logging camp, there’s genuine worry about the speed and scale of the clear-cuts outside of town. Last year, the Biden administration rolled back one of the latest attempts to exempt the Tongass from the national Roadless Rule, this time by President Donald Trump.

For some people on Prince of Wales Island, the move by Biden brought hope that large-scale logging would stop.

“I was so excited,” said Mark Figelski, who made his home here in Naukati in 2014 after purchasing 4 acres sight-unseen in a state land auction. “I thought, ‘Oh, for sure. Now we’re gonna get — you’re gonna cut this off.’”

But the logging here did not stop. If anything, it’s accelerated.

Naukati’s residents now watch excavators and logging trucks clear large swaths of trees on their doorstep faster than ever before. As he tells it, Figelski moved to Naukati for his son, who was diagnosed with autism. He wanted a place where his child could get invested in a small, tight-knit community.

Here in the rainforest, he gets much of his food for his family from the land. He forages for berries and mushrooms, hunts deer, and fishes for salmon and halibut. For him, protecting the Tongass is personal.

But Figelski wants people to know that splashy federal policy initiatives often don’t tell the whole story.

Left: Remnants of old-growth forest lay on the ground in a clear cut near Naukati Bay, Alaska in September 2021. Right: Mark Figelski looks out over a clear cut south of Kahli Cove roughly five miles northwest of his home in Naukati Bay, Alaska on Prince of Wales Island in September 2021. The area was among the parcels swapped from U.S. Forest Service to Alaska Mental Health Trust ownership under a federal law passed in 2017. Photos by Eric Stone.

“When you think about what a victory everybody was celebrating about the Roadless Rule coming back, but really it means nothing if there’s a backdoor,” Figelski said as he drove his compact SUV through an immense clear-cut near his home. “This is one big-ass loophole.”

Figeslki said he’s not anti-logging nor are his neighbors, many having worked in the forest products industry themselves. But they believe in responsible forestry. And what they’re seeing, they say, isn’t responsible and could take away their way of life. Aggressive logging can destroy habitat for deer and ruin the spawning habitat for salmon.

And, of course, it’s not just bad for Naukati. The world depends on the Tongass, seen by many as “the lungs of North America,” a vital resource for sequestering carbon. The Tongass currently holds 44 percent of all the carbon stored by U.S. national forests. While other forests often burn in wildfires, releasing the carbon sequestered by photosynthesis right back into the atmosphere, the rainforest of Southeast Alaska is different. Forest fires are relatively rare here. In fact, climatologists believe this part of the world will generally get wetter as global temperatures rise. So the Tongass isn’t just a carbon sink, it is a steady one — vital to the long-term fight against climate change. The Tongass “is some of the most carbon-dense, old-growth rainforest in the world,” said Dominick DellaSala, an ecologist and chief scientist at the nonprofit Wild Heritage. “Even more dense in carbon storage [per acre] than the tropical rainforest … What it comes down to is really abusive use of the rainforest. When you come in and you clear-cut — and you take out all the trees over an area as large as 40 acres, in some cases, private lands, it’s even larger — that just takes out all of the value of the forest. You lose most of the carbon, which goes up into the atmosphere.”

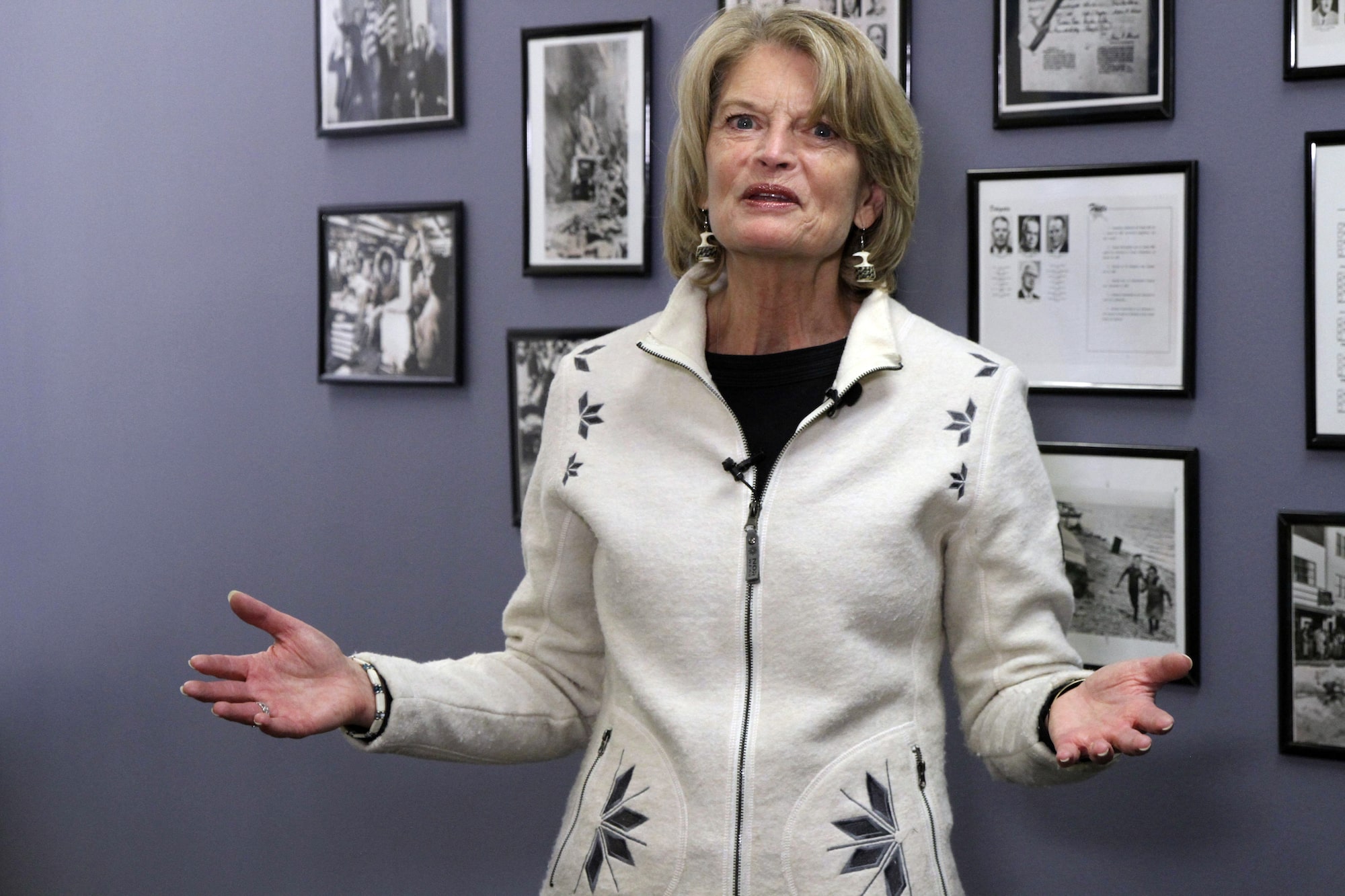

The land exchange between the Forest Service and Mental Health Trust was more than a decade in the making. But much of its legislative success can be laid at the feet of the U.S. Republican Senator from Alaska, Lisa Murkowski. She and her staff spent years in talks to design a transfer of Tongass federal lands into the hands of the trust.

She’s heard concerns about accelerated logging but said protections are in place.

“It’s not as if the Alaska Mental Health Trust has some ability to go outside of the built-in protections that are already provided by law,” Murkowski said in an interview, saying the exchange will be a net benefit to the communities in and around the land swap.

But people in the region like Joe Carl are more skeptical. He owned a small sawmill and raised oysters outside of Naukati. In an interview in late 2021, shortly before he passed away, he expressed concern over what would become of the area surrounding his home: Now that the land isn’t owned by the federal government, timber crews are able to harvest trees more liberally because of the state of Alaska’s more flexible timber rules.

In his view, he said, the Mental Health Trust is not a responsible steward of the land it was granted.

He pointed to rules about buffers. Those are the no-cut zones around streams and rivers to prevent clear-cuts from destroying salmon spawning habitat in freshwater.

“Their buffers on their streams are bigger,” Carl said of Forest Service regulators who oversee timber harvests in the federally owned land of the Tongass National Forest. “Now, they do a good job compared to all these other places I’ve logged for, where we’re getting the last tree, and see you later.”

Public lands managed by the Forest Service have stronger protections for streams and waterways than required under Alaska law. That means once land is removed from the Tongass it can be more aggressively harvested, which arguably leads to less sustainable practices.

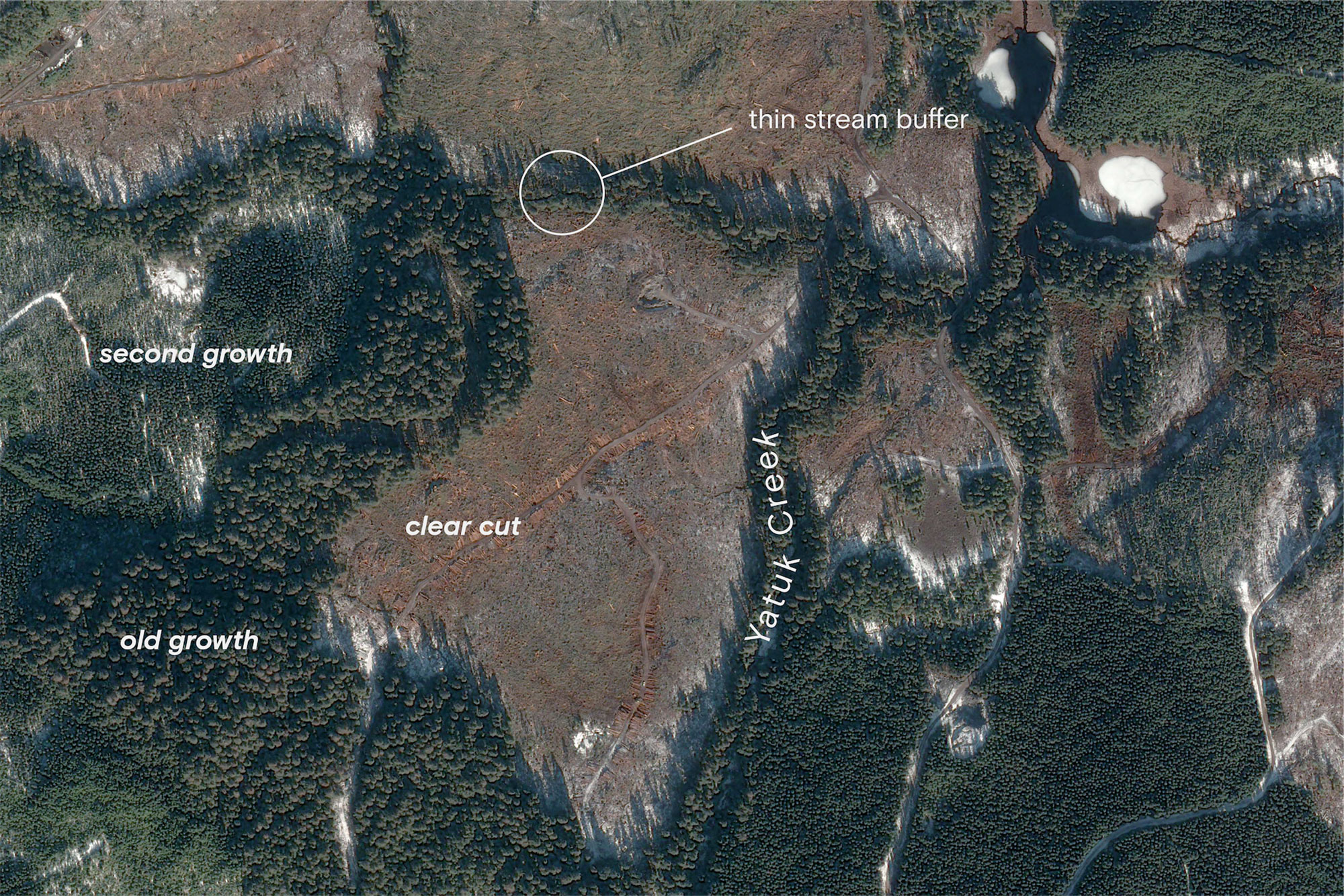

The Forest Service requires a 100-foot buffer around salmon-producing streams. But under Alaska law, the Mental Health Trust can leave buffers as narrow as 66 feet on the land it has logged.

State fisheries biologist Mark Minnillo grew up on Prince of Wales Island. It’s his job to walk lands identified for logging and point out salmon habitat before the first tree is cut. It’s a contentious issue in a place where the salmon run is a means to feeding families; it’s more than a recreational pastime.

“Unless they have anadromous fish in them, they receive no protection,” Minnillo said, referring to fish who live in the sea but return to freshwater to spawn, such as salmon. “So yes, the operator’s following what’s in the Forest Resources and Practices Act [Alaska’s statute regulating logging], but those protections are definitely less than what the Forest Service uses.”

State biologists and foresters still walk the land and point out places where logging buffers should be widened to keep clear-cuts further away from salmon and trout habitat. That’s because the thin line of trees left standing are often later felled by high winds and heavy rains and erosion. But any protections past the 66-foot no-cut zone would be voluntary, explains Joel Nudelman, a veteran state forester of two decades.

“It is ultimately up to the landowner to determine where they’re going to harvest,” he said.

The impact of this logging is palpable in the forests surrounding Naukati. Streams that people here rely on to feed their families with salmon show signs of degradation. Commercial salmon fisheries also rely on these waterways, and make up a sizable chunk of the local economy. Much more than, say timber, which an analysis of state data by a regional development group says provides about 320 jobs across this region — about a tenth of what Southeast Alaska’s commercial fishing industry employs.

According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s anadromous waters catalog, 124 streams cross the forested parcels transferred from the Forest Service to outside stakeholders, like the Mental Health Trust. These waterways serve as spawning and rearing grounds for salmon. Satellite imagery confirms the suspicions of observers like Carl: Buffers along fish-bearing streams on trust and private lands toe the 66-foot limit afforded by Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources.

But the land exchange is good business for the region’s logging industry — or what’s left of it. And it’s almost universally supported by Alaska’s elected leaders.

“When we looked to how we could allow for an exchange that would protect areas within Forest Service lands, while at the same time taking care of an obligation to a subset of Alaskans as people that are cared for under the Alaska Mental Health Trust, we figured that this was a symbiotic relationship,” Senator Murkowski said in an interview.

She successfully inserted language authorizing the land exchange with the Alaska Mental Health Trust in a must-pass piece of legislation. It was signed by President Trump in 2017. Along Yatuk Creek, about a few miles northeast from Naukati, Minnillo, the state fisheries biologist, walks through an area being actively logged by crews contracted by the trust. Logs are stacked high along the side of a road waiting to be hauled off to the mill. Trees lie in and across the salmon-producing stream.

This likely wouldn’t have happened if it were logged under the federal rules that regulate the Tongass.

Some blowdown is to be expected, even in untouched old growth. It can help shade the creeks, Minnillo said, keeping water temperatures low — just as salmon here in Alaska like it. But too much, and stream banks start to erode. Felled trees can block salmon and trout from making their way upstream. Waterways get more turbid.

In knee-high rubber boots, the biologist strides across a bridge overlooking the creek. Salmon in greenish-brown spawning colors rest in an eddy downstream, waiting for just the right time to scamper up the creek and complete their journey.

“This is some of the blowdown that’s happened in this area,” he said, pointing to trees within the legally mandated 66-foot ribbon of uncut timber. That small buffer often translates to two or three trees on each side of the stream. In many places, though, it’s functionally zero — because those that are left standing by loggers are felled by Mother Nature.

But the worst damage is yet to come. With the bank now exposed, it’ll likely collapse, in this area that gets about 100 inches of rain a year.

“You can see this one here with this big exposed root wad, you’re going to get a lot of erosion off of that,” he said, pointing to a gash in the creek bed. “You can see what you end up with if this creek gets higher flows. It’s going to erode.”

As we talk, a logger — Chris — shows up. We pause so Minnillo can pitch him on fixing up the stream bank. But it’s all voluntary. State officials can’t compel him to do more to protect a salmon-rich stream like this one.

The Mental Health Trust’s land exchange is the most recent land swap affecting the Tongass, finalized this year. But it is nowhere near the size or scale of the 2014 transfer of 70,000 acres to a regional Alaska Native corporation.

Sealaska is one of a dozen regional Alaska Native corporations created a half-century ago by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, or ANCSA, of 1971. Corporations received lands to invest in and pay out to Alaska Native shareholders.

Some invested in oil exploration, others mining, and many leveraged lucrative federal defense contracts. Sealaska logged on lands across Prince of Wales Island. It was always controversial, but it allowed the group to pay dividends to Alaska Native shareholders.

Some of those lands were meant for cultural sites and preservation. “But the economics of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act didn’t leave too many options available to the original board,” said Patrick Anderson, who is Tlingit and a former Sealaska director on the board from 1989 to 2016.

“Part of the pressures that we really felt were the dividend pressures from shareholders,” he said.

Those are the annual payments to the corporation’s 20,000-odd Native shareholders.

Sealaska dominated the region’s logging industry between 2014 and 2021. According to timber harvest plans submitted to the state, Sealaska applied to log at least 18,000 acres of land it received in the 2014 transfer. No other entity came close to this volume.

Sealaska representatives declined to comment on the volume of its timber harvests, saying it was proprietary information.

Sealaska renounced commercial logging in 2021, a blow to the region’s timber industry. But that doesn’t mean more land transfers aren’t being considered. In 2019, Sealaska invested at least $500,000 in a campaign to create five new Alaska Native corporations that would be allowed to select federal lands from the Tongass. The new corporation shareholders would be descendants of the five village populations originally left out of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

That effort, introduced on Capitol Hill last fall, is being supported by Alaska’s Congressional delegation, including Senator Murkowski, who helped engineer Sealaska’s 2014 land swap.

“The timber industry in Southeast [Alaska] has struggled for years,” Murkowski said from Washington, D.C. “And it’s been because of a lack of supply from the Forest Service.”

Those descendents from the five villages have created the group Alaska Natives Without Land. The organization has released maps that include tracts on Prince of Wales Island — land where they do not have direct historical ties. If approved, the bill would allow these shareholders to use the land for economic activities, including logging and tourism. The mining rights, however, would belong to Sealaska.

Tribal leaders on Prince of Wales Island say they are sympathetic to the landless communities’ situation but are worried that their forestlands will be targeted for their timber.

“We support these communities that want to gain access to a resource that other communities got in the past,” said Clinton Cook, president of the Craig Tribal Association on the island.

But “hopefully they’ll look at more areas in their community,” he said, and not on Prince of Wales Island that already has a network of logging roads and a legacy of clear-cut logging.

The Tongass National Forest is often lauded as an asset for all people in the United States. But for those whose homelands were nationalized it’s a legacy of stolen land.

“When they set aside the 16 million-acre Tongass out of the total 25 million acres, that fueled a lot of early rage against the government,” Anderson said of the early 20th-century creation of the Tongass. “While I know the Tongass is a tremendous public resource, it was taken from the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian people.”

All for what he calls “a minuscule amount of money” — $7.5 million — paid in 1968 and only after Tlingit and Haida tribal leaders sued the federal government for forcibly taking its lands to create the Tongass in the early 1900s.

“What we gave up in rights, should be at least acknowledged by the rest of the United States,” he said. “And maybe some of the investment that then goes into the fighting that occurs, all of the public policy that occurs, should be invested in developing other aspects of the Alaska Native world.”

Tucked into a narrow fjord that serves as the gateway for ferry passengers, a historic water-powered boatworks greets those coming to Prince of Wales Island. It has serviced the region’s fishing fleet since the 1940s.

Sam Romey has owned the Wolf Creek Boatworks for nearly 30 years, leasing the land it’s on from the Forest Service. Previous owners have leased it since 1939.

But the land was included in the exchange with the Mental Health Trust. Now, Romey is locked in a legal battle with the state of Alaska, which defends the trust in court.

Romey feared the ridges above his land would be clear-cut. Then he got a public notice in February 2022 confirming his fears.

“It’s in the backyard, the side yard, it’s everywhere,” he said in a phone interview.

The trust says it intends to cut some 800 acres of old-growth forest and 29 acres of young growth, some of which comes uncomfortably close to Romey’s historic structures.

“They’re planning to log that entire mountainside,” he said. There’s a salmon-bearing stream that powers the boatworks. He had to be mindful of it when it was managed by the federal foresters.

“All of a sudden,” he said, “we go from ‘preserve the forest, take care of it — you can’t cut a tree down without asking the Forest Service’ — to ‘we’re going to mow the entire mountainside down’,” he said.

This project is a partnership between Grist, a nonprofit media organization covering climate justice and sustainability for a national audience, CoastAlaska, a nonprofit consortium of several public radio stations in Southeast Alaska, and Earthrise Media, which supports environmental journalism with satellite imagery and data analysis. The story was written and reported by Jacob Resneck, regional news director at CoastAlaska based in Juneau, Alaska, and Eric Stone, who reports and hosts for KRBD, a public radio station in Ketchikan, Alaska. Data reporting was done by Clayton Aldern at Grist and Edward Boyda of Earthrise.

Still photography for the story was done by Eric Stone. Drone photography and video provided by SEAKdrones LLC. Jacky Myint handled design and development. Art direction by Teresa Chin. Video editing by Daniel Penner. Megan Merrigan and Christian Skotte handled promotion.

The project was edited by Grist executive editor Katherine Bagley and Grist senior editor Katherine Lanpher. It was copy edited by Grist reporter Shannon Osaka and environmental justice fellow Julia Kane. The project was fact-checked by Grist news and politics fellow Lina Tran.

The project was made possible by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.